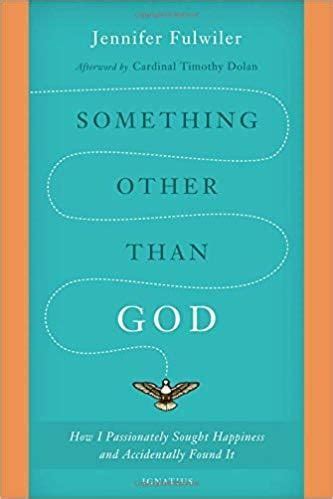

Something Other Than God: How I Passionately Sought Happiness and Accidentally Found It. By Jennifer Fulwiler. Ignatius Press, 2014.

“All that we call human history… [is] the long, terrible story of man trying to find something other than God which will make him happy.”

–C.S. Lewis

Conversion stories often get a bad rap. In many popular culture venues, conversion stories revolve around an unpleasant person muddling about in sin and iniquity, who suddenly accepts Jesus as his personal Lord and Savior, and then becomes an entirely different person after embracing Christianity. Often, conversion stories come across as preachy and didactic, and sometimes the emphasis on piety and newfound perfection of character come across as inaccessible to the average person.

Jennifer Fulwiler’s book Something Other Than God: How I Passionately Sought Happiness and Accidentally Found Itis a conversion story, but a very fresh and unique one. This book is a memoir of Fulwiler’s developing religious beliefs, opening with her childhood in a nonreligious family in a highly Christian community. The story then moves into early adulthood, as she grows up unconcerned and amiably dismissive of religious belief. Along the way, she falls in love with a terrific guy, gets married, starts a family, wrestles with the struggles of making a living, and deals with serious health problems.

On their own, these points could make for an interesting autobiography, specially for someone with Fulwiler’s unique narrative voice. However, the driving force of this story is Fulwiler’s growing interest in religion, that leads her to start a blog asking questions about faith, and then to explore Christianity, especially focusing on Catholicism. Though the story is told from her perspective, the book is also about the spiritual journey of Fulwiler’s husband as well.

Fulwiler seems surprised and thrilled that her life took the directions it did. Fulwiler opens her book with a scene set at a summer camp with proselytizing evangelical counselors. In the opening scenes, friends of Fulwiler’s are cornered and asked if they are ready to commit their lives to Jesus Christ. Fulwiler was under a lot of peer pressure to make a profession of faith, but at that point in her life she simply didn’t believe in anything religious. She writes:

“Before that moment, I’d never defined myself by my views on religion. I grew up aware of the obvious fact that the physical world around us is all there is, and it never occurred to me that such a normal outlook even needed its own word. But as I listened to the giggles and yelps of the girls through the closed cabin door, I realized that my beliefs differed so radically and fundamentally from other people’s beliefs that it would impact every area of my life. For the first time, I assigned to myself a label, a single word that defined me: atheist. The concept settled within me as perfectly as puzzle pieces snapping into place, and for the first time in days, I broke into a broad, exuberant smile.” (p. 11).

Something Other Than God consistently comes across as being uncensored and surprisingly honest. Frequently, Fulwiler expresses an old opinion or past action that comes across as being precisely the sort of thing that most people would prefer to keep buried decently in the past. It’s Fulwiler’s strength of prose and personality that makes Something Other Than God so compulsively readable. She is unafraid to display her personal flaws (or at least, those aspects of herself she feels willing to reveal), and her portraits of herself and her personal life are always engaging. She continually reiterates the fact that given her upbringing, she seems to be an unlikely person to start a career as a religious blogger and speaker. She mentions one early anecdote from growing up, describing her mother’s reaction to one of her actions:

“But even though she [Fulwiler’s mother] wasn’t religious, and she didn’t seem to have a problem with my dad’s atheism, I would occasionally find out the hard way that she harbored a certain respect for religion. When our public school invited a Christian group to offer pocket-sized Bibles to students, I grabbed one from the stack to use for arts and crafts projects. At home, I tore out some pages, cut them into little stars and hearts, and glued them to poster board as part of a collage that now hung on the main wall in my room.

When my dad noticed it, he thought it was creative. When my mom walked in with an overflowing basket to put away my clean clothes, she gasped when she saw my artwork, almost dropping the laundry. She stared at it as if I’d spray painted swastikas on my wall and told me in no uncertain terms that I was not to cut up any more Bibles.” (p. 12).

Inside her family, her father praised skeptical thinking and intellectual independence. Growing up, Fulwiler’s family’s distrust of organized religion caused her to feel like an outcast in a heavily Christian community:

“Other people’s religious hang-ups were the only possible explanation for the fact that I could count my friends on one hand.

There had been tension surrounding this issue from the first day we’d moved into the neighborhood, when two families stopped by and asked us where we went to church. My first day at school, I was asked the same question four more times. My excuse that we were “still looking for a church home” had been getting less effective since we hadn’t managed to find one in three years. Now, thanks to the camp debacle, it was all out on the table: We didn’t go to church. We were never going to church. We were not a Christian family. And now, I had no one to hang out with.” (pp. 13-14).

As Fulwiler progresses on her faith journey, she soon discovers an amazingly supportive and helpful community of believers. However, while she readily admits that there are lots of very nice religious people out there, for much of the book she is not quite ready to become a part of that community herself.

I will not reveal too many more details about the anecdotes and details in this book, because too many revelations would spoil the engrossing character development. Fulwiler makes herself and her family sympathetic without coming on too strong, and recounts the little annoyances, career problems, and potential budget busters that have the potential to turn her life upside-down.

Something Other Than God is filled with perceptive insights into the nature of faith and religion, how overt proselytizing can be less effective than intellectual pursuits and the power of the Holy Spirit, and how important caring parents and spouses can be to surviving in a difficult world. Fulwiler illustrates the contempt and suspicion with which much of secular society views religion, particularly fervent Christians. How Fulwiler went from seeing religious people as odd and alien, to understanding them, to becoming one of them, is not just and entertaining story, it is an inspiring one.

–Chris Chan