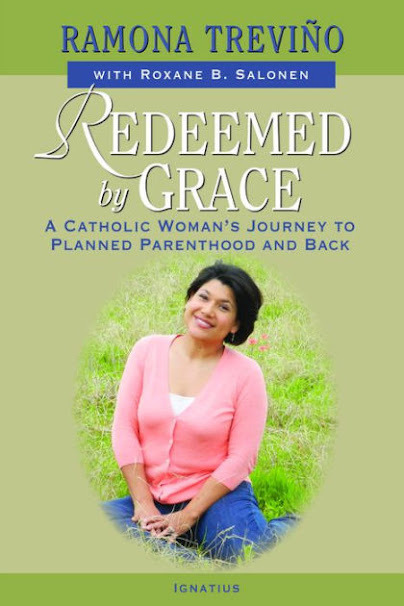

Redeemed by Grace: A Catholic Woman’s Journey to Planned Parenthood and Back. By Ramona Treviño, Ignatius Press, 2015.

Ramona Treviño’s memoir is the story of a woman who took paths in life that she later regretted, and then made every effort to start afresh and move in the right direction. Treviño’s presentation of her childhood is a predominantly happy one full of religious faith, but around the age of sixteen she started dating a handsome young man and became pregnant by him. Treviño writes in clear and heartfelt prose, describing her life and her changing emotions with clear and genuine prose. As she writes, one gets the feeling that she is trying to unburden herself of unpleasant memories, but as the book progresses one realizes that Treviño has written this book to reach out to readers who might need help with a difficult situation.

Treviño traces her spiritual journey and changing career paths, tracing her life story and explaining why it traveled in the directions that it did. She writes:

“Looking back at my life as a child, I can see that even though it was not ideal, it’s very obvious that I was loved.

When I became pregnant at sixteen, I learned the meaning of unconditional love. It was unconditional love that made it possible for me to say yes to my pregnancy. It was that same love that ruled out the possibility of abortion. Abortionwas not a word we had ever used in our house, nor considered.

Reflecting back, it makes sense why I would be so willing to sacrifice my life for the life of my baby. Although my parents had their struggles, they taught my sister and me the meaning of love and sacrifice through their actions. My mother always put our needs before her own, making sure our basic needs of food and clothing were always met. She did the very best she could with her situation. My father, though suffering from his own demons, always came through for our family when we needed him the most and found a way to provide. He never turned his back on me when I made bad choices or made life difficult.

Both parents taught me the meaning of love and faith in an unconditional kind of way, by welcoming a grandchild without batting an eye. God had always provided for us so why would this time be any different? Their daughter was having a baby, and there was nothing else to be said about it. If only other young women could have parents as forgiving as mine.” (p. 141).

The pregnancy led to a daughter, and Treviño married the father of her child in a secular ceremony. The marriage was not a happy one, and it eventually became an abusive one. Treviño traces the devastating psychological effects that her emotionally manipulative and physically violent husband had on her, and the great effort it took to escape his control. A divorce followed, and Treviño struggled as a single mother for a while until finally meeting the man who would become her second husband, who she would later marry in the Church.

Treviño’s personal life is frequently referred to throughout the book, and her second husband and children consistently come across as sources of joy and strength. It is Treviño’s professional life that eventually causes her deep and profound torment.

Treviño’s description of her professional life will no doubt provoke some controversy, but by providing a human face and a complex soul to her situation, it will cause both supporters and opponents of Planned Parenthood to look at the organization in a new way. Treviño started working at a Planned Parenthood clinic, eventually becoming a manager there. The clinic dispensed medications and other materials, and performed examinations, but although clients were frequently referred to other venues for abortions, the surgical procedure was never actually performed at Treviño’s clinic.

For a while, Treviño had some minor qualms about her work, but quieted her conscience and did not think too closely about the ramifications of Planned Parenthood’s policies and approaches. Over the years, Treviño began to feel increasingly uncomfortable with her job, and this sense of unease was exacerbated by her discovery of a Catholic radio station that led her to reevaluate her life and future in unexpectedly emotional and disturbing ways.

When describing her experiences, Treviño writes:

“For the last several months, I had been feeling restless at my job– especially now that God had been revealing so many truths to me. The only time I felt at peace was on the weekends. I would go home and get restored only to face each Tuesday morning with an escalating sense of dread.

When I pulled into my driveway in Trenton, I stopped the car and stayed in my seat. I couldn’t go in– not yet. With the keys still in the ignition, I turned on the radio. I wanted to listen again to the Catholic station I had discovered just four months earlier. The programming both attracted and challenged me. The featured discussions seemed to resonate with truth, and that captivated me; yet at the same time, they left me troubled. I wasn’t sure if I was ready to confront the possibility that I might have taken some wrong turns.

After all, I was the manager of a contraception and abortion-referral clinic. For three years I had been trying to convince myself that my job didn’t have anything to do with abortions– or at least didn’t make me directly responsible for them– despite the hundreds of girls I had directed each year to another facility to terminate their pregnancies.” (pp. 1-2).

Whatever one thinks about abortion and contraception, Treviño’s approach to these subjects is not that of a polemicist or a pundit, but as a woman who is simply and honestly recounting her own experiences and reactions to a situation. Her job was destroying her, and only by leaving could she regain her mental, spiritual, and psychological health. Tied to Treviño’s recovery is her re-appreciation of her religious faith, and a re-evaluation of the morality of her job, along with her relationship with God.

“God had never walked away from me. I was the one who had drifted. I had allowed my sin to blind me from truth. And I had had a hand in abortions– a direct hand. How many girls had I watched walk out of my care and into places that would kill the sweet, innocent lives growing inside them and depending on them for survival? Those girls had come to me with a sliver of hope, searching for a better solution, and I had taken that sliver and smashed it to pieces.

I couldn’t wash my hands of any of it; I knew that now. But I also sensed that on the other side of my raw pain, a loving father waited with open arms.

I love you, and I want to bring you to the other side of this; but first, I need you really to look at what you’ve done and own up to it.

It wasn’t too late. I was here, I was still alive, and that meant there was still time. God had spared me so that I could get to this very moment and have a chance to repent and save my soul.” (p. 5).

Due to the subject matter, this may be a polarizing book, but Treviño comes across as a thoroughly sincere and likeable woman, describing her experiences with sadness and residual anguish, but not anger. There is no self-righteousness or condemnation in her work, but only a pure, honest emotion. Throughout the book is the pure feeling of Treviño saying, “I want to help.” This book is meant to help others, through telling the story of a woman who found a way to help herself.

–Chris Chan